PLEASECOMECLOSER: Babak Saed’s Installations

Babak

Saed places value on realizing his installations in public spaces. His

works are either temporary – or as public art – permanent

installations; art in real space. He is a conceptual artist who works

with language as his medium.

Babak

Saed places value on realizing his installations in public spaces. His

works are either temporary – or as public art – permanent

installations; art in real space. He is a conceptual artist who works

with language as his medium. ”Every installation makes reference to the main objective of the institution in question. And at the same time it responds to the existing architecture and engages in a dialog with it. On the one hand, the work must adapt to the space, but it must also give it character. In my works, I basically formulate the same principle over and over again – but always in new ways. Communication is my theme,“ says Babak Saed.

Running up- and downstairs

This does not mean that the viewer will be able to read these works or understand what they are communicating immediately. He must work his way into them, become acquainted with them, often running up- and downstairs in the process. He will continually be reading something new, and he will have difficulty reading the texts because their legibility is not identical with interpretability. Saed makes use of language – the alphabets of language – as rhetorical figures, as metaphors that open up new, inner images to the viewer. Babak Saed plays – in a manner of speaking – with the „memory code,“ as neurobiologists call it these days. Ideas, thoughts and memories flicker in our brains in the form of electric signals. The normal procedures of legibility are disturbed in Babak Saed’s art works, new contents arise continually in the viewer’s brain, so to speak, since legibility is no longer based in tried and true habit. Babak Saed confuses us by asking us questions that are not formulated as such, but rather – because they are statements – almost have the character of an ex cathedra pronouncement. Babak Saed always conceives of texts as questions, questions that he puts to us. Babak

Saed grew up embedded in Islamic culture language and, starting in

childhood, has always seen the treatment of language and letters as a

centrally important element of visual art. The reader may be reminded

here of the prohibition of images, Arabic and Persian calligraphy, but

also of the contemporary form of textual statements integrated with

letters of the alphabet in the field of contemporary visual arts: Rose

Naumann, Joseph Kusuth, Jenny Holzer, Lawrence Weiner and Thomas Locher

come to mind. In her essay on an installation by Babak Saed, the art

historian Barbara Weidle also points out the connections with running

TV text trailers and text-messaging. Babak Saed masters contemporary

communicativity to an incredible extent, unhinging it from its capacity

for linguistic coherence. This is what provides his works on contentual

connotations with a truly fascinating context.

Babak

Saed grew up embedded in Islamic culture language and, starting in

childhood, has always seen the treatment of language and letters as a

centrally important element of visual art. The reader may be reminded

here of the prohibition of images, Arabic and Persian calligraphy, but

also of the contemporary form of textual statements integrated with

letters of the alphabet in the field of contemporary visual arts: Rose

Naumann, Joseph Kusuth, Jenny Holzer, Lawrence Weiner and Thomas Locher

come to mind. In her essay on an installation by Babak Saed, the art

historian Barbara Weidle also points out the connections with running

TV text trailers and text-messaging. Babak Saed masters contemporary

communicativity to an incredible extent, unhinging it from its capacity

for linguistic coherence. This is what provides his works on contentual

connotations with a truly fascinating context.

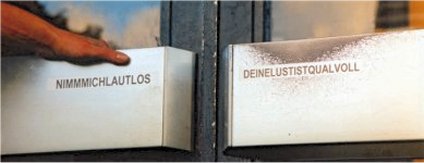

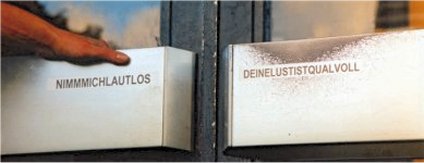

The cock’s crow – in thirty languages

One of his works, on display at the Deutsche Welle (Germany’s international broadcaster) in Bonn, is audiovisual: it consists of two sentences and an acoustic part. The lettering is on two opposite walls. A push button has been installed under one of the two sentences. When the visitor pushes it, one hears a rooster’s crow thirty times - in thirty different languages: the selection of languages in which Deutsche Welle broadcasts its programs. The sentences run: KOMMENSIERUHIGNÄHER (i.e. PLEASECOMECLOSEROVERHERE) and GEHENSIERUHIGRUEBER (i.e. FEELFREETOGOTOOVERTHERE). The anchoring of these onomatopoetic forms in this specifically human mode of human perception is – paradoxically – based in the very diverse ways in which the rooster’s crow is represented in all languages. Saed knows very well that we perceive the same world in different ways and interpret it differently, in accordance with our respective cultural background and our identity. He therefore sees this particular work as a symbol of our alternity, our aspect of difference.

In 2007, Babak Saed created a text installation, After Babel, on the glass facades of the Academy of Fine Arts on Berlin's Pariser Platz. He transformed the building's celebrated glass facade into a colorful map of the world by means of many different languages and an abundance of sentences in different scripts, to draw attention to the connection between identity, community and language. In doing so, Babak Saed asked himself the question: „Is language a means of exclusion of outsiders, or of rapprochement, of integration?“ We might pursue the thought further by asking, is the same language a hindrance to understanding? Is the view through the lens of another language onto our own perhaps the appropriate means for rediscovering the possibilities inherent in language?

A small niche, but with no repetitions

Babak Saed has selected a small niche within contempoary visual arts for himself. But the observer is surprised time and again at his ability to adapt to new environments, so that repetitions are for all intents and purposes eliminated. As a conceptual artist, Babak Saed goes far beyond the rationality of words and language, which he dissolves in favor of an non-rational legibility. In this way, he creates not only immense contentual tensions, but also formal ones. The difficulty of reading compels the viewer to start over again and again, to continually read differently, or makes it possible for him to read off words differing from those in the sentences presented to him. Thus, a multivalence of expression arises whenever the observer himself

separates the words and slowly works them out again to understand the

text faster and better. This leads him to a new way of perceiving, a

new comprehension, another multivalency of meaning. This element of

variability prevents his statements from becoming phrase-like or

hackneyed. Babak Saed does not seek adages, turns of speech nor does he

seek functional expressions, twin forms, rhetorical figures. Metaphor

is his true love.

Thus, a multivalence of expression arises whenever the observer himself

separates the words and slowly works them out again to understand the

text faster and better. This leads him to a new way of perceiving, a

new comprehension, another multivalency of meaning. This element of

variability prevents his statements from becoming phrase-like or

hackneyed. Babak Saed does not seek adages, turns of speech nor does he

seek functional expressions, twin forms, rhetorical figures. Metaphor

is his true love.

Powerful, concentrated essences

Prof. Dr. phil. Dieter Ronte

is an art historian and artistic director of the Frohner Forum of the Krems Art Gallery and Center in Austria. He was Director of the Bonn Museum of Art until the beginning of 2008.

is an art historian and artistic director of the Frohner Forum of the Krems Art Gallery and Center in Austria. He was Director of the Bonn Museum of Art until the beginning of 2008.

Translation: Ani Jinpa Lhamo

Copyright: Goethe-Institut, Online-Redaktion

Any questions about this article? Please write to us!

online-redaktion@goethe.de

online-redaktion@goethe.de

October 2008